When Michelle Nguyen answers the phone to discuss her paintings, she ends up talking almost entirely about books. Jamaica Kincaid, Ted Cohen, John Berger, Roberto Calasso, and Jenny Odell were some of the literary names dropped—writers who collectively cover everything from art history to the philosophical underpinnings of jokes. The dizzy, reference-heavy, and fast-paced conversation is somewhat reminiscent of Nguyen’s paintings—dense panoramas of foliage and figures competing for attention. “I want to create artwork that people have to stare at for a while,” she says of her crowded canvases. “It rewards you more the more time you spend with it.”

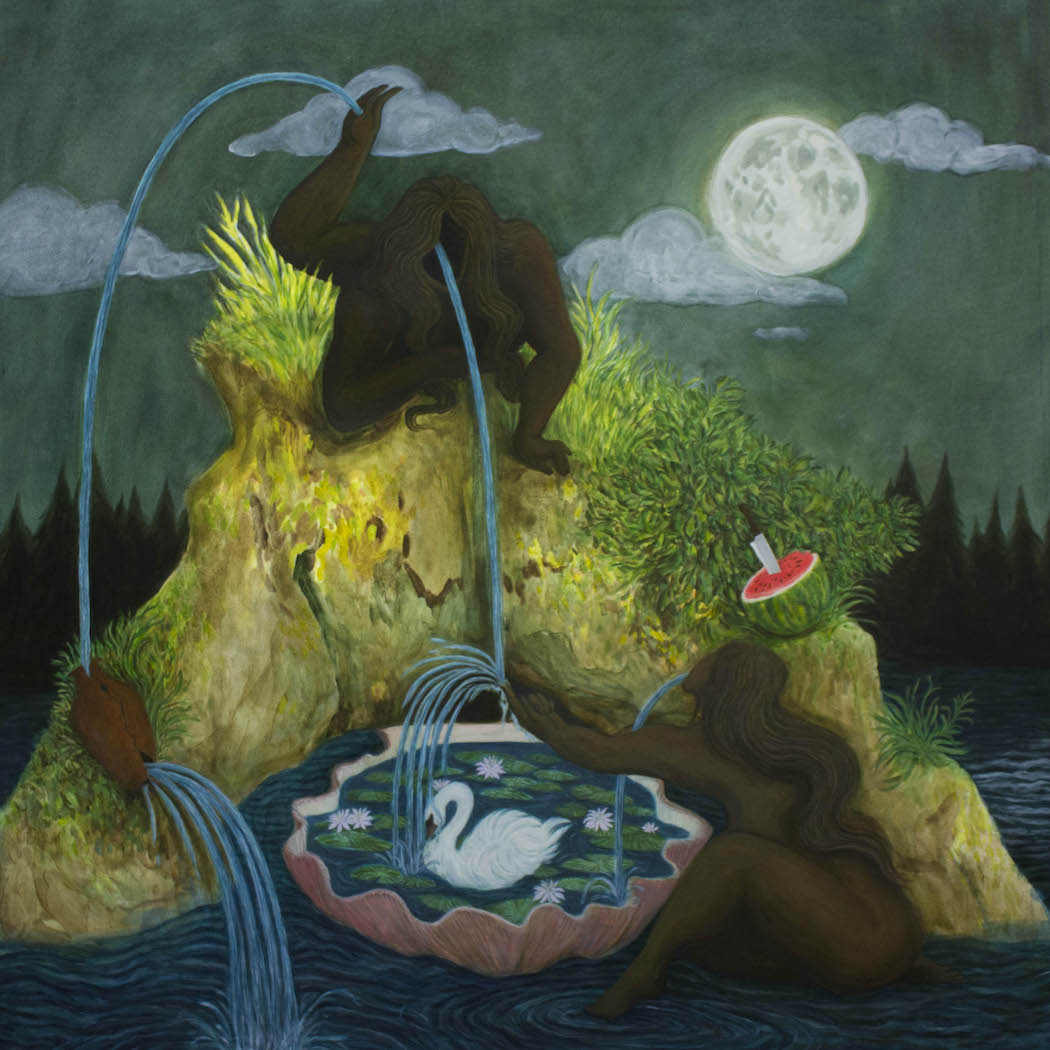

Spending time with any of Nguyen’s paintings, one could come across figures from Greek mythology, volcanic eruptions, tiny horses, giant swans, square watermelons, and, lately, Jell-O. These paintings operate the same way dreams do: full of disjointed images and tangled memories, but always radiating with meaning.

Nguyen, who works in clay and on paper as well as with paint, attended an arts-oriented high school in Toronto before moving to Vancouver to study at the University of British Columbia. Rather than pursue a fine arts degree, though, she took advantage of the varied courses on offer: science, philosophy, and environmental design. “Everything can influence your art,” she says. “I just wanted to be open that way.” Nguyen kept her painting practice alive, though, even in the eye of a stormy academic schedule. “I always found a way to fit painting into my life,” she continues. “In first year, when I was living in the dorm room, I remember lifting my bed up really high and measuring how big a canvas I could fit down there. I turned it into a studio space.” Today, Nguyen has a proper studio, where she works on two to three paintings at a time, sometimes bouncing between mediums to keep her momentum fresh.

As joyfully random as the components can appear, Nguyen’s paintings tend to circle around common themes. “I would describe the body of work I am working on right now as contemporary memento mori,” she says. “I have always been interested in the history of death rituals.” Medical history also fascinates, as well as providing a sense of reassurance: “I think it makes me more optimistic to read about how stupid we were back then, and we are still here now.” For the artist, the discomfort evoked by death and sickness creates a space that’s ripe for exploration. “I think we are taught to push away a lot of negative emotions instead of taking the time to think about them and process them,” she explains. “That is something I have always wanted to do in my work: talk about grief and mourning. And how integral that is to the human experience.”

Even while delving into prickly areas of the psyche, Nguyen’s work remains seductive and strangely sweet. It’s a matter of balance, where every pretty visual is tempered with something a little off. Finely painted vases appear overgrown with fungi, and jovial, picnic-ready watermelons are stuck with large kitchen knives. Viewers of Nguyen’s work can never get too comfortable—even the size and composition of the paintings are designed to be disquieting. Painting crowds on large canvases is a way for Nguyen to flip the power dynamic inherent in the act of looking. “If you look at [most] paintings, it is always so passive how these figures are posed,” she says. “I wanted to find a way to give power to the figure instead; this idea of crowds and having the viewer being outnumbered is one of the ways I thought about doing it.”

Nguyen’s crowded dreamscapes have taken on a new layer of weirdness in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. “They definitely hit a different way now,” she admits. If Nguyen wants to reward viewers for their attention, pre-coronavirus nostalgia is now part of the gift basket. It’s hard to look at one of her paintings, teeming with people, and not long for dance floors and humid summer streets. Or a full-on Bacchanal.

It’s thanks to Nguyen that her figures have such strong lives of their own: “Some of these pieces have women hiding in brambles and stuff—this idea that they have some sort of agency,” she muses. “Like if they want to be seen, they will let themselves be seen, but otherwise they have that safety of nature, of wilderness, to keep them safe and held.” But, even as we mortals project our desires onto them, the figures in Nguyen’s two-dimensional world remain deliciously enigmatic—always dancing, always lurking. Always, it seems, a bit more in touch with what makes life electric.

Painting credits, in order of appearance:

“Ecotone,” 2018. Oil and oil pastel on canvas. 65 x 48 inches.

“Mourning Room,” 2021. Oil on canvas. 58 x 54 inches.

“The Wedding Party,” 2018. Oil and oil pastel on canvas. 60 x 50 inches.

“Fruiting Body,” 2020. Oil on canvas. 30 x 23 inches.

“A Prayer for Safe Passage,”2020. Oil on canvas. 36 x 36 inches.

“Harpies Nesting,” 2019. Oil on canvas. 72 x 57 inches.

“Water Feature I,” 2020. Oil on canvas. 30 x 30 inches.

“Water Feature II,” 2020. Oil on canvas. 43 x 43.5 inches.